The Gothic Revival & Notre-Dame

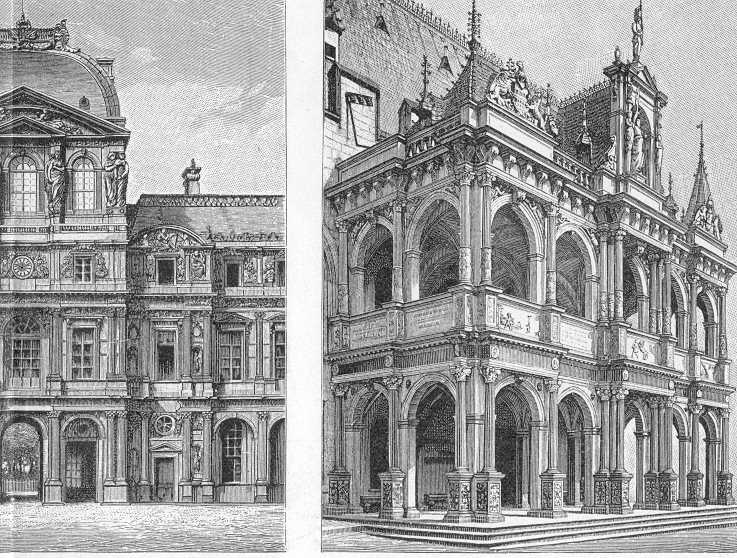

Gothic architecture evolved from the Romanesque around 1100 AD and reached its height in the mid-1400s. In the 1800s, when Hugo wrote his book, Gothic had given way to the Renaissance. By then Parisians considered medieval buildings vulgar, deformed monstrosities. Calling a building Gothic was an insult, a reference to Goth and Vandal Germanic tribes considered barbarians.

Paris Gothic history was being torn down in the name of more respectable, if not more profitable, projects.

Hugo was alarmed. He believed architecture had reached its pinnacle during the Gothic era, writing, “Indeed, from the beginning of things down to the fifteenth century of the Christian era inclusive, architecture was the great book of humanity, the chief expression of man in his various stages of development, whether as force or as intellect.” He loved Gothic Paris and wanted its structures preserved. Notre-Dame’s towers, he argued, were symbols of a glorious past. For Hugo, Renaissance architects and their buildings had nothing to offer.

But Notre-Dame in 1829 was crumbling. The cathedral was used a gunpowder factory during the 1789 – 1799 French Revolution and heavily damaged. Its largest stones were earmarked for bridge foundations. Hugo feared that, like so many of the city’s other gothic structures, Notre-Dame would soon be demolished.

He wrote:

The novel, Notre-Dame de Paris, was published in January 1831 to critical acclaim.

The book’s success brought thousands of French from the countryside and other cities to Paris to visit the building Hugo so lovingly described. They wanted to see firsthand where Quasimodo leaped to save Esmerelda from the gallows, where Frollo conspired with the King of France, where a sad soul carved fate in a tower wall. What the public found was a cathedral in danger of collapse. As Hugo anticipated, readers concluded Parisians didn’t appreciate the building’s heroic inner beauty, its strength, its character. Quasimodo was a metaphor for the building, which wasn’t lost on the novel’s fans. The public outcry to save Notre-Dame Cathedral was deafening and defining.

Restoration began in 1844. Today, it’s hard to separate book from building. Novel and cathedral are so intertwined, so reinforcing of each other, they’ve become inseparable. It’s a magical relationship that architects would do well to study. Hugo wrapped a stealth behavioral intervention inside a love story embedded in architecture. Like nested Russian dolls, Notre-Dame de Paris is a story within a story within a story. Outwardly, it’s save the girl. Inwardly, the hidden payload is save the building. Hugo wedded narrative to architecture and fermented intrinsically motivated behavior change on a societal scale, turning local apathy into public action.